Exhibition

Anna Jermolaewa

The Austrian Pavilion at a Glance

Anna Jermolaewa presents five selected works, divided between the rooms of the pavilion and the inner courtyard.

Rehearsal for Swan Lake (2024)-realized in collaboration with Ukrainian ballet dancer and choreographer Oksana Serheieva-refers to a memory from Jermolaewa’s teen years. In times of political unrest, for instance the death of a head of state, Soviet television replaced their regularly scheduled broadcast with Swan Lake ... in a loop sometimes for days. In Soviet cultural memory, Tchaikovsky’s famous ballet became code for a change in power. In Rehearsal for Swan Lake, a group of ballet dancers rehearse select scenes, transforming Swan Lake from a tool of censorship and distraction into a form of political protest-here, the dancers rehearse for regime change in Russia.

Live performances by Oksana Serheieva

April 20-May 5: daily at 1:30, 4:00, and 6:30 PM

May 17-September 30: every two weeks on Fri, Sat and Sun at 1:30, 4:00, and 6:30 PM

October 4‑November 17: every two weeks on Fri, Sat and Sun at 12:30, 3:00, and 5:30 PM

The Penultimate (2017) consists of a series of plants: carnations, roses, tulips, cornflowers, lotuses, saffron crocuses, jasmine, a cedar and an orange tree. Each plant represents a “color revolution”: a popular uprising referred to or symbolized by a color or floral term. With red carnations, Portugal welcomed a military putsch against its dictatorship in 1974. A flower was also used as a symbol of protest by Georgia’s Rose Revolution in 2003 and Kyrgyzstan’s Tulip Revolution in 2007. Also characterized as color revolutions: Lebanon’s Cedar Revolution of 2005, Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution of 2010, and Egypt’s Lotus Revolution of 2011. Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004, Myanmar’s Saffron Revolution of 2007, and Belarus’ unsuccessful Cornflower Revolution in 2006, their names based on the respective colors, are here represented with the color’s corresponding plant. Presented as a still life, these flowers and plants are a reminder of what undemocratic regimes fear most: an overthrow originating with the people.

In the postwar Soviet Union, people were banned from owning record albums containing popular music, especially rock or jazz from the West. For people caught with such contraband, prison time was a real possibility. In response, Soviet sound engineers developed a way to subvert the ban: they copied albums onto used X‑ray films hospitals had discarded. These X‑ray film records-nicknamed “ribs,” “music on bones,” and “bones”-were exchanged on the black market until the advent of the audio cassette tape. Ribs (2022/24) takes a sample of these Soviet recordings and returns them to their original function: displayed on a doctor’s X‑ray film viewer. In the Austrian pavilion, selected X‑ray film records will also be played once a day on a record player in the room.

In Research for Sleeping Positions (2006), Jermolaewa, in a hooded sweatshirt and winter coat, tries to find sleep on a train station bench in Vienna’s Westbahnhof. She tries multiple positions, all uncomfortable. Seventeen years earlier, when she arrived in Austria as a political refugee, she spent her first week on a bench in this station, sleeping on it every night before ending up in the refugee camp in Traiskirchen. The artist reenacts this experience but with one crucial difference: the bench now has armrests, installed as a deterrent for people trying to find rest.

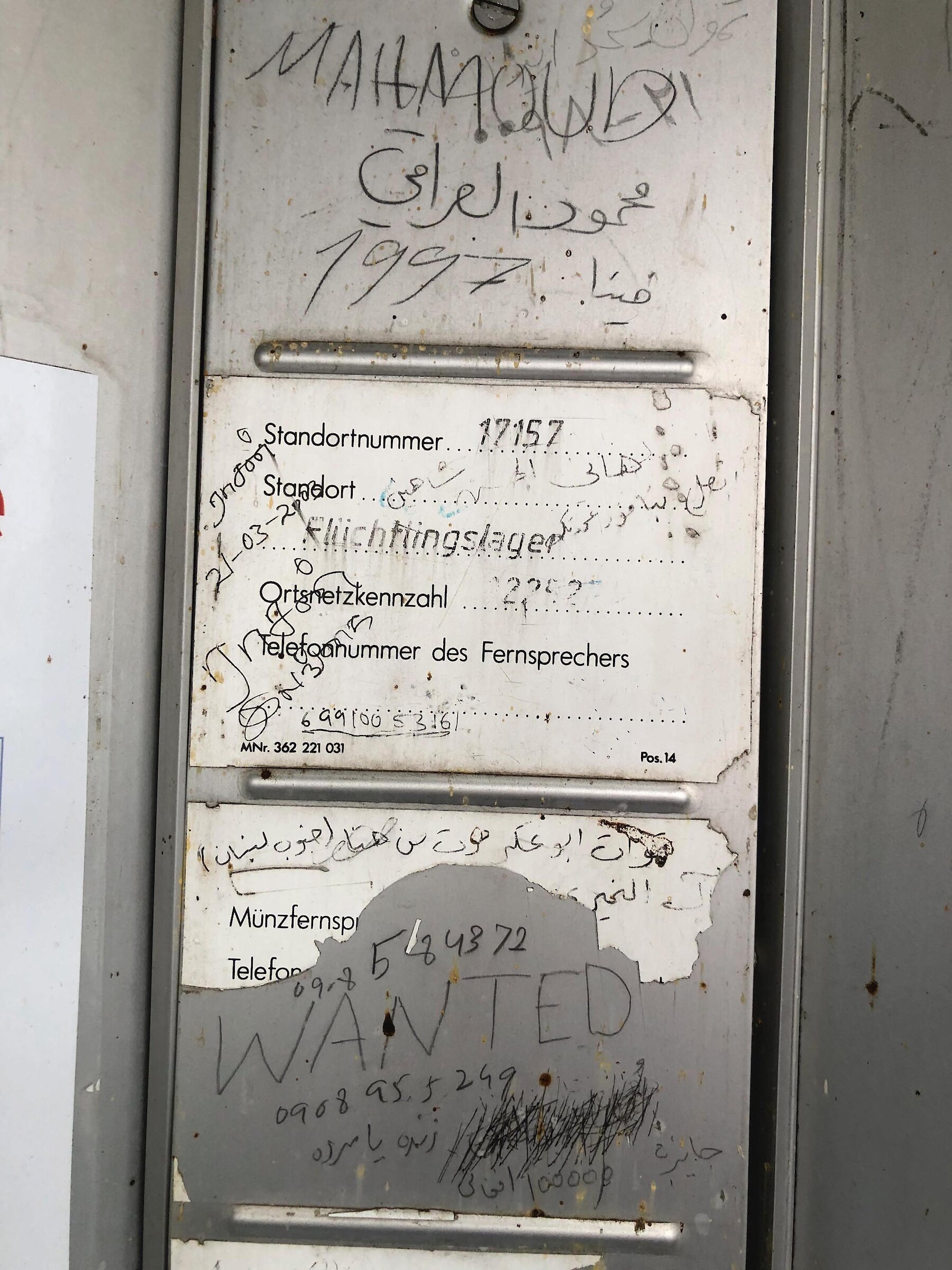

The readymade Untitled (Telephone Booths) (2024) in the inner courtyard of the pavilion is a bank of original telephone booths from the refugee camp in Traiskirchen, Austria. At first glance they may seem unremarkable, but it’s said that the most international calls made in Austria came from these six booths. Written on their walls, literally, are notes from asylum seekers. The booths are a capsule of a spectrum of emotion-the insecurity, but also hope, feit by those in transit, who have left their homes and do not know what will happen next. In 1989, Jermolaewa used these exact booths to contact her family back in Leningrad to tel1 them she’d arrived in the West. After they became obsolete due to the advent of smart phones, they were scheduled for removal. In the Giardini, they are experiencing a second life. The phones are fully functional for all pavilion visitors to use.